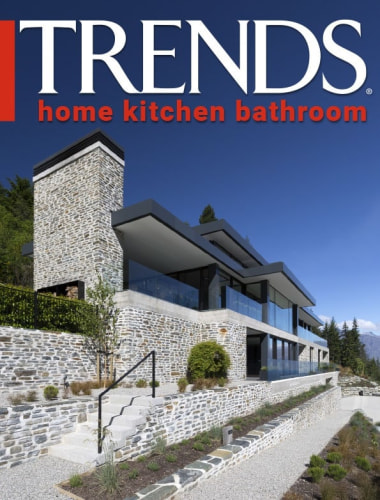

Large house on difficult steep slope is partly dug into the hillside to create a basement platform for the upper levels

This multi-level house by Mason & Wales transforms into a glass and steel pavilion on the top levels, optimising its stunning views of Queenstown

The view from the top of Queenstown Hill is truly breathtaking. However, its extremely steep gradient was certainly an issue for the architect who conceived this multi-level holiday home.

On his first visit to the site, architect Francis Whitaker says it wasn't clear how he was ever going to build a house there.

"It's an exceptionally difficult site extremely steep," he says. "It's the uppermost section of the highest subdivision in Queenstown, so it can never be built out. However, there was a problem we had no flat land to build on."

Whitaker's solution was to design a long narrow form, just one room wide, and partially submerge it into the hillside following the contours of the land.

"We had no brief from our clients for the look of the house, but because of the spatial requirements and the large number of rooms, the house simply became a series of narrow layers emerging out of the ground," the architect says. "The building actually generated itself. It's the only way it could exist."

The initial phase of the project was to cut a huge notch out of the hillside to create a flat and stable platform for the house. Peter Campbell, from local construction company Triple Star, explains the lengths they had to go to just to secure the site.

"We excavated a long, 15m-deep cut into solid rock, then inserted 150 rock anchors 14m into the exposed rock," says Campbell. "From here, we poured a huge concrete slab and two significant concrete chimneys that, with other elements, would act as bracing for the building."

This ground level forms a large basement where owners and guests park their cars, and is the main entry point to the home effectively creating a large, subterranean porte cochére.

"This level also houses a climate-controlled wine cellar, bar, and a dedicated home theatre. The garage itself is like no other it's fully tiled and lined in oak, with art on the walls. Very James Bond," Campbell says.

The architect envisaged the garage as a large car showroom, built to very high specification.

"When the homeowners are in residence, the garage door is left open and people drive directly into the bottom of the building," says Whitaker. "From here, they enter the house via a suspended glass door system into a timber-lined lobby that contains the cantilevered staircase and lift that both access the two floors above."

The next level is dedicated to the owners' children, and contains three bedrooms, a large rumpus room, the laundry, and a self-contained maid's suite. Above that, the topmost floor is effectively a one-bedroom, glass-fronted house, with huge indoor and outdoor living areas, and an even more expansive view.

This upper level is visually much lighter than the floors below, which give it the effect of floating in the sky above Queenstown. The large eaves that extend out from the pavilion reflect and accentuate the layered nature of the design.

"Overall, it's a planar design, with enormous concrete floor plates, supported by stone-clad concrete walls and chimneys that break through the floors, creating an extremely forceful composition," says Whitaker. "The top floor is a steel and glass pavilion again punctuated by the schist columns with a pop-up roof. The raised roof contributes to a high four-metre stud in this area and admits more light thanks to the clerestory windows directly underneath it."

For the home's interiors, the owner engaged Di Henshall, a specialist interior designer whom he'd worked with on three previous projects.

"The owner is a perfectionist, and was very clear from the outset what he wanted," Henshall says. "It was key that I didn't compromise the architect's vision, yet still satisfy the owner's expectations for it as a home, not as a building."

"The interiors also had to be in synergy with the landscape and the climate," she says. "Everything we did, we did to complement the naturalness of New Zealand. It is such a beautiful location that we didn't want to put anything into the house that took away from the natural beauty of the outside environment. What we added was supportive rather than obstructive."

Because the structure of the building is so powerful essentially concrete, stone and steel the interiors were softened using butt-jointed timber on the walls and ceilings.

"The timber was stained to a sophisticated grey-brown for a softened, weathered look," Henshall says. "This took time, but it was an essential part of the project, because the timber formed the main palette for the whole interior."

The designer says this was one of the biggest residential projects she'd ever undertaken.

"Because of the scale of the house, all of the furniture had to be custom made," she says.

Credit list

Architect

Builder

Roof

Wallcoverings

Countertops

Refrigerator

Heating

Spa

Interior designer and kitchen designer

Cladding

Flooring

Splashback

Kitchen sink

Ventilation

Wine fridge

Audiovisual

Awards

Story by: John Williams

Photography by: Jamie Cobel

Home kitchen bathroom commercial design

Home Trends Vol. 33/2

The design of your home is the result of your style preference, your requirements – and the influences of your site. The...

Read More