History repeats

With its bagged schist walls and gabled forms, this new house is reminiscent of historic gold-miners' huts and old stone farm buildings

No matter where you live, a glimpse into the past can tell you a lot about suitable architecture and building materials. Long before globalisation influenced residential design, homeowners made use of local materials, building houses well suited to the climate and topography.

For the early settlers and gold-miners in the Central Otago lakes district, it was the local schist stone that provided solid, well-insulated shelters. Their original huts and farm buildings also featured chalet-style roofs to deflect winter snow falls.

It's a vernacular that helped determine the design of architect Ken Warburton's own country house near Wanaka. Strict local body regulations required the house to have a pitched roof, and also specified materials that would be natural and non-reflective. But Warburton says he didn't want a heavy, dark schist house, which would look too much like many other new homes in the district.

"The solution was to use a mix of cedar boards and a bagged schist, which is similar to the early miners' huts these were covered in clay to seal the gaps between the stone. For this house, we bagged the schist with a white cement to achieve a similar effect. This treatment transformed the look of the house, introducing a highly textural element, and adding a light, warm look to the exterior."

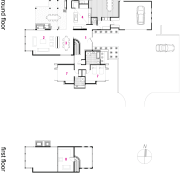

The house has other historic references. Designed as a series of linked, gabled pavilions, the architecture is reminiscent of a collection of farm buildings that could have evolved over time.

"It's a little like a country estate, which would typically include a woolshed, and a series of barns and outbuildings," says Warburton. "And like these traditional buildings, each of these forms has its own distinct identity."

Because the site is exposed to strong northeasterly winds, the main living, kitchen and master suite pavilions wrap around a sheltered, west-facing courtyard. The largest pavilion accommodates the entrance and main living area, which includes a soaring, double-height space, and a more enclosed dining area.

"Each of the gabled forms has a spacious, open interior, with a fully glazed wall maximising the sun and view," says Warburton. "But there are also low ceilings and flat-roof areas in between, where the spaces are deliberately closed in to provide a more cosy, intimate feel. These include the circulation areas, library and dining room. The contrast between the high and the low ceilings heightens the visual drama."

To provide a strong connection to the immediate landscape, most rooms open to the outdoors. The architect has also brought the exterior materials through to the interior one bagged schist wall forms a massive fireplace surround.

"I like to emphasise the importance of a fireplace," Warburton says. "Here, the fireplace becomes a strong element within the overall design of the house. Its long, cantilevered hearth, which appears to float above the floor, helps to lighten the mass of the stone, and reinforces the long front-to-rear axis."

Tiled circulation areas bordering the main living spaces play a similar role, and provide further visual continuity.

Wide openings a characteristic feature of Warburton's designs allow an easy flow through all the public spaces, and ensure there are continuous sight lines throughout the house. But the architecture also acknowledges the climate extremes of the location.

"The house is designed so that we can close off the formal dining, living room and guest wing in winter, when only my wife and I are here," says Warburton. "This allows substantial energy savings.

"Conversely, in summer, the house can be fully opened up to the outdoors, with cross ventilation helping to keep the interior cool."

Other energy-saving initiatives include double glazing, and a diesel-powered, hot water underfloor heating system.

To provide a seamless, contemporary look, Warburton designed matching New Zealand beech wood furniture pieces, including built-in cabinetry for several rooms. The cabinets have recessed, black-painted toe-kicks, which make the units appear to float above the floor.

Beech cabinetry is also a feature of the kitchen in the centre of the house. As with the adjacent library, this room is contained within its own small pavilion, which is at a 180° angle to the three large volumes.

The glazed ends of the pavilion allow plenty of natural light to flood the room. There are additional windows opening to a large terrace on the east side of the house, again ensuring this is a home for all seasons.

Credit list

Builder

Cladding

Flooring

Heating

Audiovisual system

Furniture manufacturer

Benchtops

Dishwasher

Shower fittings

Kitchen manufacturer

Roofing

Blinds

Paints

Lighting

Speakers

Kitchen cabinetry

Taps

Cooktop and ventilation

Bath

Story by: Trendsideas

Home kitchen bathroom commercial design